Geoffroy Week: Geoffroy’s Tailless Bat (Anoura geoffroyi)

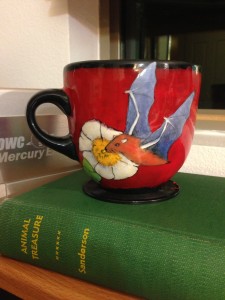

We’ve been getting an unusual amount of rain here in New Mexico where I live, and my open window admits the sound of nocturnal frogs (or toads, maybe) calling from the standing water in the median outside. I’m drinking coffee from a cup hand-painted with an illustration of a bat visiting a flower (from Rainbow Gate in Santa Fe) (this is my second one with the same design because the first broke; this one is already broken in a wabi sabi nothing-is-permanent sense, but not in a literal sense) as I finish Geoffroy Week the way it started: with a bat named for the important French naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire.

We’ve been getting an unusual amount of rain here in New Mexico where I live, and my open window admits the sound of nocturnal frogs (or toads, maybe) calling from the standing water in the median outside. I’m drinking coffee from a cup hand-painted with an illustration of a bat visiting a flower (from Rainbow Gate in Santa Fe) (this is my second one with the same design because the first broke; this one is already broken in a wabi sabi nothing-is-permanent sense, but not in a literal sense) as I finish Geoffroy Week the way it started: with a bat named for the important French naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire.

Geoffroy’s tailless bat, which is sometimes known as Geoffroy’s hairy-legged bat, lives in the neotropics from Mexico into South America. It roosts in orchards, forests, and caves near water, in colonies that include bats from other species and genera. It’s mostly nectivorous—it dines on nectar and it pollinates plants—but it also eats fruit and insects. When it alights from its roost, it does a quick back flip, and in laboratory tests, it uses echolocation to navigate obstacle courses. Wouldn’t you love to see a bat navigating an obstacle course?

The University of Miami’s website includes a page that has some charming photos and very short videos of bats, including several of this species, visiting flowers. Flowers that are pollinated by bats may be referred to as chiropterophilous, if you please. Bats that pollinate flowers have very long tongues that allow them to really dig in to their dinners. Flowers that bats pollinate tend to have larger male sex organs than those pollinated by other creatures, like hummingbirds; the reason for that may be that bats are more efficient at their pollination. (You can read about it here on the website of Science magazine.) Flowers and their pollinators have evolved so that they’re dependent on each other. This is an example of coevolution, which is what happens when two organisms affect each other’s development over time.

While this bat was named after our friend Geoffroy, it was named by John Edward Gray. If you followed the Daily Mammal’s Olympics coverage, you may recall Gray and his wife (Mrs. Gray, natch), after whom he named an antelope and who drew molluscs by the score. Naturalists have sometimes been disparaged as “stamp collectors,” but John Edward Gray was an actual philatelist as well as a prominent 19th-century naturalist; in fact, he was one of the first known collectors of stamps.

Very nice work on Geoffroy week! and good history lessons.

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed it.