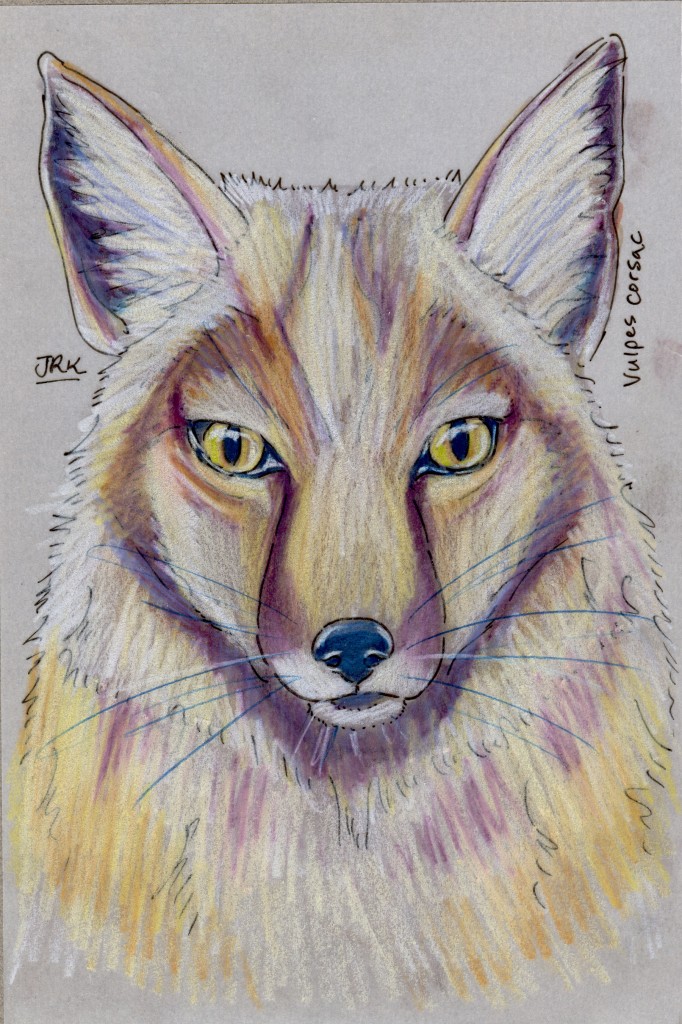

Corsac Fox (Vulpes corsac)

The corsac fox is a nomadic, nocturnal, social resident of the steppes and semi-deserts of central Asia, from Russia and other former Soviet states to Mongolia and China and down to Afghanistan and Iran. It lives in the abandoned burrows of other animals, and it eats rodents, pikas, birds, insects, and plants. Walker’s Mammal’s of the World says that “it runs with only moderate speed and can be caught by a slow dog,” which first made me feel for the fox, but then I read the following in Notes of an East Siberian Hunter, a new translation of a 19th-century work by A.A. Cherkassov:

“The corsac has exceptionally keen hearing, smell, and vision; he is an agile runner, but when dogs chase him, he gets tired soon. He is so fast on turns that when the dogs catch up to him, they cannot catch him, because he evades them and rarely ‘gets in their teeth.’ Most often he ends up disappearing into some hole. Therefore, dogs catch corsacs only by chance, when they find them still foraging in the morning on the open steppe and they have no time to hide.”

Well, I didn’t read that in the actual book, I read it in an excerpt on Google Books. The book was originally published in 1865 and has, apparently, been regarded as a classic in the Russian naturalist world since then, but it was never translated into English until this year, when Vladimir Beregovoy and Stephen Bodio issued a print-on-demand edition of their translation. (Stephen Bodio, it turns out, lives here in New Mexico). I love reading these 19th-century naturalists. They write with such verve, and with such a mix of natural lore, bemusement, and arrogance. They represent a vanished world, when it seemed there was still so much to learn, when nature seemed truly endless.

Cherkassov also discusses the methods of trapping corsacs. (They are never hunted with guns or dogs, he says, and there are only two ways to trap them.) He says that when trapped in their burrows with the exits blocked, corsacs will sometimes choose “to die of starvation rather than go into a trap.” According to Cherkassov, they can last 10 to 15 days this way:

“The corsac’s ability to endure 15 days of starvation can only be explained by his exceptional shyness, which is a distinct trait of his entire way of life. After such prolonged starvation, trapped corsacs show no signs of having taken any food. A fox trapped in a hole is much bolder than a corsac. He does not wait in the hole any longer than three days and most often goes through the trap on the second or even on the first night. Death by starvation is scarier than violent death, but taking a risk sometimes ends with an escape by lucky chance.”

There is something haunting about these images of the trapped red fox and the trapped corsac, weighing, through instinct, their odds and taking the chance that seems best.

Beautiful portrait!

I agree with your love of the 19th-century naturalists. Like other scientists of the time, they have an almost childlike innocence mixed with occasional savagery, while at the same time seeming to epitomize civilization and culture. How’d they do that?

Great piece, Jennifer!

Thanks, Ted! I don’t know exactly how they do it, but I think the language they use does a lot of the hard work for them.

Nice painting! I think you should alert Bodio to your website, since you cited his translation. It is pretty amazing what a seemingly endless variety of mammals there are. Thanks for alerting us to this fascinating subject and for doing such a great job both in the paintings and the descriptions.

Thanks! It is amazing. I keep thinking I’ve drawn all the “good” ones—but I’m always wrong! Good idea about Bodio.