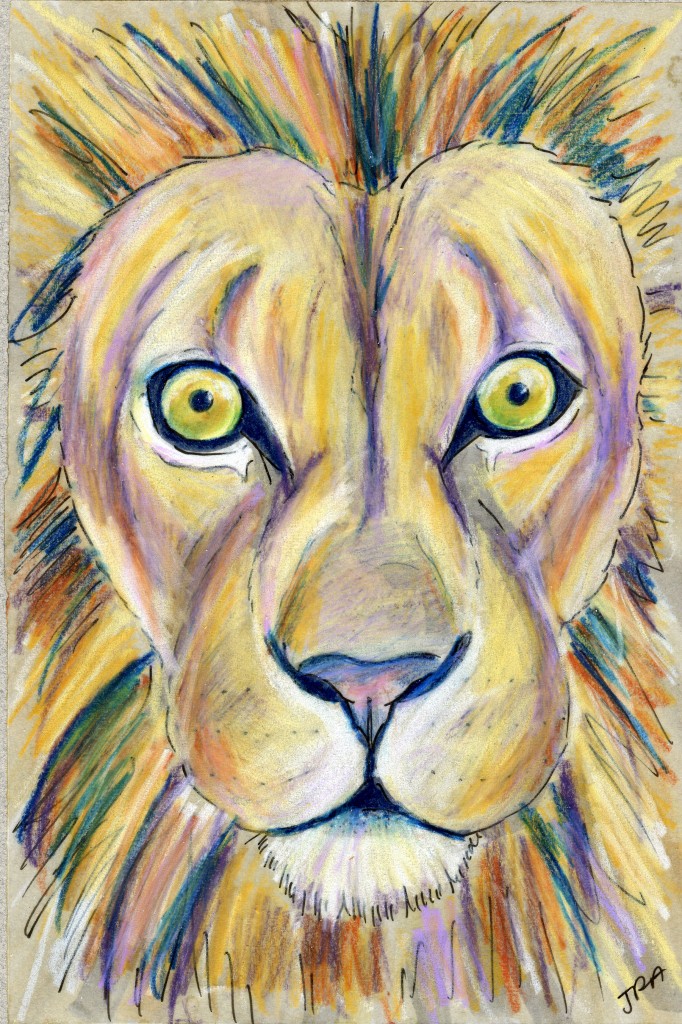

Darwin Days: Lion (Panthera leo)

It’s quite fashionable to equate the theory of evolution with Charles Darwin himself. Science magazines and books sell with covers blaring “Darwin Was Wrong,” “Was Darwin Wrong?,” and “What Darwin Got Wrong.” Meanwhile, intelligent-design and creationism proponents attack “Darwinism,” and the New York Times publishes “Darwinism Must Die So That Evolution May Live” and “Let’s Get Rid of Darwinism.” By creating an -ism, the New York Times pieces suggest, “Darwinists” devalue their own arguments, putting them on the same level as, for instance, creationism.

The fact, as far as I can tell, is that Darwin was right about many, many things, and most of those things that he was wrong about (mainly because things like genetics and continental drift hadn’t yet been discovered, and the man couldn’t do it all!) have nevertheless been built on his foundation. Many of the articles celebrating Darwin’s bicentennial point out how remarkable it is that after 150 years, On the Origin of Species is still relevant. Today we’ll talk about one of the ideas Darwin had before his time and that is still being studied and proven: sexual selection.

Basically, sexual selection refers to the favoring of certain traits solely because they are attractive to mates. As Darwin says in Chapter 4 of Origin, “This depends, not on a struggle for existence, but on a struggle between the males for possession of the females; the result is not death to the unsuccessful competitor, but few or no offspring.” To attract females, males develop showy traits like bright feathers, big antlers, or electric guitars. The reasons why females are attracted to these things in the first place are not fully known; it could be that a male with big horns, for instance, has good genes in other ways; another theory holds that if a male can thrive despite the “handicap” of a huge tail or something, he must be pretty strong.

The lion’s mane has long been a puzzle. In 1859, in Origin, Darwin wrote, “The males of carnivorous animals are already well armed; though to them and to others, special means of defence may be given through means of sexual selection, as the mane of the lion, and the hooked jaw to the salmon; for the shield may be as important for victory, as the sword or spear.” The going theory for many years was that manes protected male lions from the claws and teeth of their rivals, but now it doesn’t appear that’s true because fighting lions don’t tend to go for the head and neck in particular.

Studies in the past several years have focused on the variations in mane length and color. Researchers found that the luxuriousness of a lion’s mane depended on its climate: lower, hotter, and more humid climates meant skimpier, lighter-colored manes because it can get hot under all that hair. The researchers were also surprised to learn that manes continue developing after the lion’s sexual prime has come and gone. In the hottest places, older males are the only ones with manes to write home about. It makes me wonder if there could be a reverse sexual selection going on there: if you don’t have a mane in a hot place, does it indicate that you’re younger and therefore more virile? I don’t know.

Scientists also fooled around with trying to lure both male and female lions with fake dummy lions of varying mane lengths. They found that males approached the shorter-maned dummies 9 out of 10 times, and females approached the longer-maned ones 13 out of 14 times. The males that intrigued the females intimidated the other males, in other words.

Here’s a book I read part of once that postulates that all human creative culture—from art to architecture to comedy to writing books, etc.—is the result of sexual selection. In other words, men do cool things because chicks dig it: The Mating Mind by Geoffrey Miller.

Very thoughtful and interesting. Nice drawing, too. Leo somehow reminds me of Minnie!

Hmm…could it be the eyes? (Minnie is my dog. She’s black with orange eyes. Her nickname at the shelter was Crazy Eyes.)

What a beauty! Leo and Minnie!