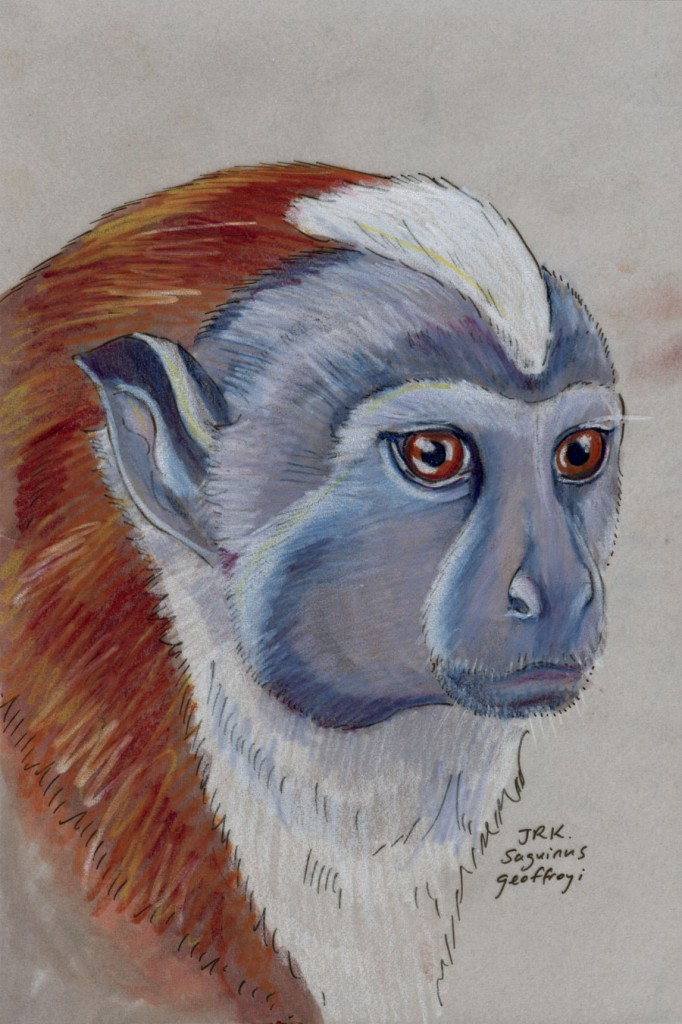

Geoffroy Week: Rufous-naped Tamarin (Saguinus geoffroyi)

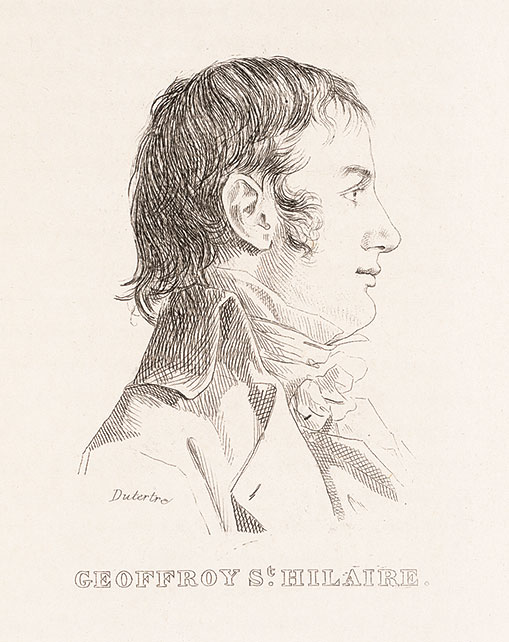

In 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt in a bid to interfere with British trade routes and generally prove his might. (He did everything generally—get it?) Along with tens of thousands of soldiers, he took some 150 scientists and other intellectuals who studied Egyptian culture, history, geology, and wildlife. Napoleon invited both Cuvier and Geoffroy along; only Geoffroy went. He ended up being stranded there for three years, but he came back with dozens of cases of specimens, including ancient mummified animals pillaged from Egyptian museums. If you’ve been following Geoffroy Week, you know a little about the mostly friendly rivalry between Cuvier and Geoffroy. Cuvier studied the mummified specimens that Geoffroy brought home and concluded that since they were identical to contemporary animals, species must not change over time. In other words, he used Geoffroy’s own specimens to argue against Geoffroy’s theory. This argument continued between the men for decades. In 1838, Geoffroy wrote in a letter to George Sand:

“According to Cuvier, God has performed this immense miracle once and for all in order never to go back on it…That was quite simply the grossest stupidity that it was possible to propose to human credulity…Animal forms are…unceasingly variable.”

Of course, the specimens were only thousands of years old, not enough for evolutionary changes to be apparent, but Cuvier still thought he’d got one over on Geoffroy. In Lamarck’s Evolution: Two Centuries of Genius and Jealousy, Ross Honeywill writes of a conversation between Lamarck, the famous French naturalist, who shared Geoffroy’s views on evolution, and Faujas, a French geologist:

“Careful not to insult Lamarck’s great friend, Faujas remarked casually, ‘Geoffroy should have thought twice before accepting Napoleon’s invitation to accompany him on the invasion of Egypt.’ He went on, ‘It afforded Cuvier the perfect opportunity to claim even more power in Geoffroy’s absence and it also delivered to Cuvier the very specimens he so badly needed to discredit your work.’

“Lamarck was not offended and replied, ‘Yes, I agree. I counseled Geoffroy against going but he is a great one for adventure.'”

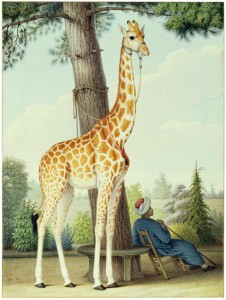

In 1827, Geoffroy had another encounter with Egypt in the form of Zarafa, a giraffe given to King Charles X by Muhammad Ali, the viceroy of Egypt. Zarafa landed in Marseilles and then walked 550 miles to Paris, accompanied by a small herd of cows that produced milk for her to drink, Egyptian handlers, and a French delegation led by Geoffroy, who organized the journey, ordered a coat and shoes for the giraffe, and walked before her into each village along the way.

Zarafa was the first giraffe to set hoof in France, and she was a sensation, inspiring trends in fashion, housewares, and even hairdos. One hundred thousand people visited her in six months. A group of six Osage Indians from Missouri traveled to France around the same time and created a similar frisson among the Parisians, who were in thrall to anything exotic that summer.

(If you want to know more about Zarafa, who outlived Geoffroy in the end, Zarafa: A Giraffe’s True Story, from Deep in Africa to the Heart of Paris by Michael Allin is supposed to be pretty good. In 2012 an animated film about Zarafa came out in France, and there are at least a couple of children’s books about the giraffe.)

None of this, however, has a thing to do with today’s mammal, the rufous-naped tamarin, which is also called Geoffroy’s tamarin. It’s a tiny monkey, less than a foot long and weighing under half a pound, and it lives in Panama and Colombia. It’s polyandrous, which means that each female mates with many males, and it eats insects, eggs, frogs, fruit, and flowers (along with a few other small flora and fauna). This tamarin is very stylish looking. With its red mantle and white mohawk, it reminds me of a ruler from some dystopian sci-fi world. It sleeps in nests—probably made by squirrels—in trees that are either dense with leaves or covered with vines.